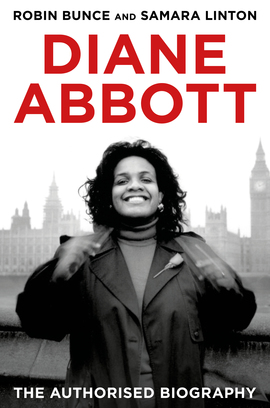

Diane Abbott: The Authorised Biography hit the shelves yesterday, and to celebrate we're sharing the introduction from the book.

A winter election is a sure sign of crisis. Like December 1923 and February 1974, December 2019 was a tumultuous time for politics.

The political and constitutional crisis of 2019 was profound: an illegal prorogation of Parliament; a government ruling with no majority; and a constitution bent out of shape by Brexit. Despite this, the feeling in Hackney on election day was optimistic. Situated next to a hipster barbershop populated exclusively by men with monumental beards, and opposite a Lebanese deli, the mood in Diane Abbott’s election office was focused, a little nervous, but definitely upbeat. The view a few hours before the polls closed was that the local campaign had been good, although it was agreed that the result of the national campaign was impossible to gauge.

In one corner a young computer scientist and social media influencer curates Abbott’s Instagram. ‘I usually use Lota Grotesque,’ she explains. ‘It’s Labour’s font, so it’s part of the brand.’ Apparently, while Abbott is routinely vilified on Twitter, her reception on Instagram is altogether warmer – presumably due to the demographic of the platform’s users. Another staffer co-ordinates last-minute leafleting, while Abbott’s agent is out of the office running people to and from polling stations. Electioneering in Hackney has none of the glamour of The West Wing, nor the muted chic of House of Cards. Boxes of campaign material lie here and there, activists come and go, some wearing bright red ‘Vote Labour’ hats provided by UNISON. Between the ‘Vote Labour’ posters, some Labour red tinsel adds a touch of seasonal cheer.

In one corner a young computer scientist and social media influencer curates Abbott’s Instagram. ‘I usually use Lota Grotesque,’ she explains. ‘It’s Labour’s font, so it’s part of the brand.’ Apparently, while Abbott is routinely vilified on Twitter, her reception on Instagram is altogether warmer – presumably due to the demographic of the platform’s users. Another staffer co-ordinates last-minute leafleting, while Abbott’s agent is out of the office running people to and from polling stations. Electioneering in Hackney has none of the glamour of The West Wing, nor the muted chic of House of Cards. Boxes of campaign material lie here and there, activists come and go, some wearing bright red ‘Vote Labour’ hats provided by UNISON. Between the ‘Vote Labour’ posters, some Labour red tinsel adds a touch of seasonal cheer.

Abbott’s arrival at 4 p.m. changes the atmosphere: the focused silence is replaced by a buzz of enthusiasm. It has been a long campaign, the phoney war having started in the summer, and, as far as Abbott is concerned it has been ‘an exceptionally dirty campaign’. Yet Abbott seems energised. At the end of November 2019, the Tories were something like twelve points ahead, but in the final fortnight the lead had narrowed. Six hours before the polls closed, Abbott’s view was that the election was too close to call, a view shared by respected psephologist John Curtice, at least up until polling day. Although Labour was still behind in the polls, there was a chance of a minority government and, with it, Abbott’s promotion to one of the great offices of state.

Abbott’s politics are complex. She embraced socialism while an undergraduate at Cambridge University, studying black history for the first time with Jack Pole and Professor Robert Fogel. On returning to London, she became involved with the Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent, an umbrella group of black and Asian women radicals which had grown out of the Black Power movement and embraced anti-imperialism and black womanism. In the 1980s Abbott was a councillor in Westminster where she fought for better housing, the provision of crèches, and honesty with the local population about their prospects in the event of nuclear attack – which led to her being labelled as a member of the ‘loony left’. Since her time at Cambridge she has campaigned on issues of representation. And it was her work with the Labour Party Black Sections campaign that propelled her into Parliament. As an MP she has been a constant critic of unaccountable executive power; of the consequences of privatisation; of draconian immigration laws; and of illiberal measures which compromise civil rights in the name of security.

Abbott’s politics may be complex, but her essential beliefs can be expressed simply. Speaking to a group of young people in Parliament in December 2013, she linked her politics to her background. ‘I came down from Cambridge with my degree,’ she recalls, ‘and I really felt the world was my oyster. As a young undergraduate, I didn’t have the debt, buying a home was perfectly in reach, and getting a decent job was perfectly within reach.’6 Abbott regards herself as being a beneficiary of the ‘enabling state’. She received the best education that money could buy for free. ‘My education was completely free. From start to finish. There were no tuition fees, I got a maintenance grant, and it was very easy to get jobs in the holidays.’

Having left university, she bought a house in central London, with the help of a loan from her local council. Due to a buoyant labour market, she was able to gain well-paid work first in the civil service, then the National Council of Civil Liberties, and latterly in the media. In fact, her varied career was a testament to the numerous opportunities for young people in the years after she graduated.

Abbott’s early life was not without difficulties: ‘I had to deal with a lot more overt racism than is around today, but, you know, some things were better.’ However, almost four decades later, ‘young people today face a very grim prospect’.8 Debt, the housing crisis and the dwindling number of secure well-paid jobs mean that ‘Generation Z’ have few of the opportunities of those born before 1980. And while all young people have been disadvantaged by these changes, those who are likely to have been hit worst are young people of colour.

For Abbott, this narrowing of prospects is ‘largely because of decisions made by politicians’. Abbott argues that there’s a simple equation at the heart of politics: ‘What you put into it is what you get out of it. If they [politicians] feel that people who look like you don’t care, don’t ask hard questions, and above all do not vote they will do that they like to you.’

In a country where democracy has become increasingly winner-takes-all, and progressively majoritarian, Abbott offers an important corrective. Minority representation at all levels of politics, and throughout civil society is crucial because it is the best way of defending and advancing minority rights. And democracy without minority rights is no democracy at all.

Election day on Thursday 12 December 2019 did not bring Labour’s hoped-for breakthrough. The Conservatives swept to power with a majority of eighty, while Labour lost sixty seats, many in its traditional heartlands.

Nonetheless, the election may well have been a breakthrough in a different way. The parliament that was elected in 2019 is the most diverse in British history, containing more black, Asian and female MPs than ever before. This achievement is part of Abbott’s legacy. As the first black woman ever elected to the British Parliament, she changed the face of British politics for good.

Diane Abbott: The Authorised Biography is out now: grab your copy here!