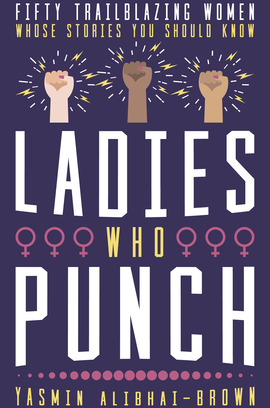

To celebrate the publication of Yasmin Alibhai-Brown's book Ladies Who Punch, take a look at an extract celebrating a pioneering woman: in this case, Victorian author and scientist Beatrix Potter...

Beatrix Potter was a children's writer, scientist, eco-farmer and conservationist.

In 2016, a new 50p coin featuring Peter Rabbit was minted to honour ‘the author of some of the best-loved stories for children that have ever been written’.

It was a tarnished tribute. Beatrix Potter did far more than make up stories about cute farm creatures in bow ties and bonnets. The coin, lovely as it was, diminished and infantilised a woman of many parts. Potter did pen those dear books, which still delight kids today. More than 250 million copies have been sold worldwide. But she was also a serious botanist and conservationist, a farmer, a dedicated keeper of some of the most precious parts of the English countryside, a businesswoman.

The accomplished lady did all that without any formal education, which she regarded as a blessing: ‘Thank goodness I was never sent there [to school] – it would have rubbed off some of the originality.’ She should be made the saint of autodidacticism.

Her father, Rupert, was a distinguished lawyer, and Helen, her mother, the daughter of a wealthy merchant. The couple were definitively upper-middle-class Victorians. In pictures they look rich and dour. Beatrix and her younger brother Bertram were raised by servants, taught by governesses. Customarily, the boy was sent to boarding school. Thus denied contact with children of her own age, Beatrix lived in her own world, making up animal stories. The family had many pets, and visits so the Lake District gave them an enduring love of nature and critters and art. Her parents encouraged the pursuits.

As she grew older, Potter became interested in serious science, botany in particular and fungi most of all. By her early twenties, she was studying specimens under a microscope, making accurate drawings and reading papers. According to her biographer Linda Lear:

Her interest in drawing and painting mushrooms, or fungi, began as a passion for painting beautiful specimens wherever she found them … She was drawn to fungi first by their ephemeral fairy qualities and then by the variety of their shape and colour and the challenge they posed to watercolour techniques.

She produced 350 accurate, delicate pictures of fungi, mosses and spores. Art was leading her to science.

Believing she could make her name as a scientist, Potter began engaging with amateur enthusiasts and learned botanists. Potter’s uncle, Sir Henry Enfield Roscoe, a reputable academic, got Beatrix into Kew Gardens to do proper research, though botanists at Kew were dismissive of the knowledgeable, persistent woman who tried to engage with them.

Her first scientific paper, ‘On the Germination of the Spores of the Agaricineae’, was submitted to the Linnean Society for natural history in 1897. However, ‘as a woman, she wasn’t allowed to be present at the reading of her own paper. It wasn’t published (also due to her gender) although scientists today have confirmed her theories as being correct.’ Some scientists, not all.

Back in the 1890s, Potter was not only a major irritant to egotistical specialists, she was caught up in blistering intellectual disputes about the natural histories of lichens and algae. She apparently admired the work of Swiss botanist Simon Schwendener and was persuaded that his theories had merit. George Murray of the Natural History Museum had his own ideas and was, she noted, ‘high-handedly contemptuous’ of rivals and alternative theories.

Her surviving letters and journal continue to divide opinion, finds Nic Fleming of the BBC: ‘Some have suggested that she was a pioneering scientist whose contributions were suppressed by the patriarchal Victorian scientific establishment. Others have described her as an ambitious, well-connected amateur with an overinflated sense

of her work’s importance – one that fooled later writers into believing she was breaking new ground.’

Nicholas Money of Miami University disdains the idea that such opinions are sexist ‘myths’. To him, the reality is that she was merely ‘an enthusiastic amateur’. He concedes, however, that Potter’s ‘paintings of fungi and their fruit bodies were beautiful and scientifically accurate – and were later used to help identify mushrooms’.

To Lear too, Beatrix Potter was a dabbler, an intelligent but bored woman who sought out interests. She had no ambition to be a mycologist but does deserve credit ‘for her openness to speculation, her careful and thoughtful observation of several species of lichens and algae and her courage as a female to speculate in a professional field’. A little patronising, don’t you think?

Science writer Tom Wakeford takes Potter and the forces against her much more seriously: ‘The soon-to-be-famous children’s illustrator was hounded out of biology by the closed ranks and narrow minds of London’s top scientific institutes,’ he says. Their members refused to accept ‘Beatrix’s evidence that the curious living encrustations, known as lichens, on tree-trunks, seashores and walls, were made up of not one but two organisms in intimate liaison’.

I am inclined to agree with Wakeford. Beatrix’s womanhood was the problem, not her science. She walked away from a subject she loved. Reluctantly, I’m sure. That unconscious bias is still playing out today too in departments across universities and in major science institutions.

In 1891, aged twenty-five, Beatrix Potter noted in her diary: ‘Genius – like murder – will out.’

Not without run-ins and fightbacks. Beatrix’s first book, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, was turned down by several publishers. She used her own money to print and distribute it. The fine drawings and charming stories were a hit with the public: she had arrived. As early as 1903, she patented a Peter Rabbit doll. Great timing, great business sense.

From then until 1913, Beatrix wrote and illustrated her most famous tales and made enough money to become a woman of independent means, free of parental control. There were reasons why this mattered so much to her. In her early twenties, Beatrix’s parents tried to find her a suitable husband. She refused them all. Her mother never forgave her for wanting to be more than a wife.

The person Potter trusted most as an author was Norman Warne, her editor and the brother of her publisher. Over time, ‘their creative synergy, and their respect for each other had deepened into love. Beatrix saw herself as one of Jane Austen’s heroines whose story had “finally come right”.’ In 1905, they got engaged. Her snobby parents were apoplectic. He was in trade and beneath them in every way. They insisted on a six month

separation.

Tragically, Norman died just one month before they could marry. Heartbroken, Beatrix moved to Cumbria, where she stayed for the rest of her life. After 1913, there were no more books. She became a sheep breeder and passionate eco-farmer, in today’s parlance.

In that same year she married William Heelis, a ‘gentle, quiet man who shared not her love of fantasy, but her real love of the land’. Having her own money freed her for ever from her controlling parents and Victorian England’s rigid mores.

Potter and Heelis became dedicated custodians of the Lake District. Beatrix owned fourteen working farms. When she died in 1943, she left a legacy of which the books are but a part. Over 4,000 acres went to the National Trust. It is one of the biggest bequests left to the trust, ever.

Now, how about another commemorative Beatrix Potter coin depicting a Lepiota aspera, a beautiful mushroom that she found and painted with scientific accuracy? Or a vintage microscope? So she is memorialised as a serious scientist as well as an artist of loveable woodland creatures.

Yasmin's book, Ladies Who Punch, is out in hardback. Take a look at it here.