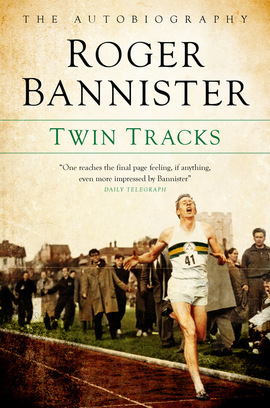

Twin Tracks - The Autobiography, by Sir Roger Bannister

Sir Roger Bannister has sadly passed away at the age of 88 – this is his story. Twin Tracks tells the full story of the talent and dedication that made him not just one of the most celebrated athletes of the last century but also a distinguished doctor, neurologist and one of the nation's best-loved public figures.

Enjoy the sample chapter below:

Click here to read more.

My running career can be neatly divided into two parts: before and after Helsinki. My failure to win the 1,500m gold medal in Helsinki, when I had been the favourite, was a shattering blow. All of my past planning over six  years seemed to have been wasted. It was a huge knock to my pride, shattering to my friends and family and to the Great British public.

years seemed to have been wasted. It was a huge knock to my pride, shattering to my friends and family and to the Great British public.

Some have said that one element of courage is dignity in the face of adversity, and I now had plenty of practice. It was some time before I could screw up my self-belief but within a month I had decided to continue racing until 1954, when I would face the Empire Games and the European Games. If I could win these titles, then I would feel that my training ideas had been vindicated. Paying back my supporters may be a cliché but many clichés have a kernel of truth. I knew even then that part of my life would be inextricably entwined with running and would never detach itself from sport, despite the hard years ahead that I knew I would need to devote to my training as a neurologist.

I felt it was necessary to prove that my attitudes towards training had been right and hence restore the faith that had been so shaken by my Olympic defeat. I could accept being beaten in the Olympics – that had happened to many stronger favourites than me. What I objected to was that my defeat was taken by so many as proof that my way of training was wrong.

Whether we as athletes liked it or not, the four-minute mile had become rather like an Everest – a challenge to the human spirit. It was a barrier that seemed to defy all attempts to break it, an irksome reminder that man’s striving might be in vain. The Scandinavians, with their almost excessive reverence for the magic of sport, called it the ‘Dream Mile’.

An interest in running races, and in particular the mile, dates back to the mid-nineteenth century, when mile races were won in about 4 minutes 20 seconds, and the discussion ranged over whether a mile in under four minutes was possible. There was an achingly slow progress in improvement in the record, until a British runner, W. G. George, set up the new record of 4 minutes 10 seconds in 1885. The next big step forward came during the Second World War, when the three Swedes Arne Andersson, Gunder Hägg and Lennart Strand repeatedly raced against each other over the mile, week in, week out. Whichever of the three was least strong would be pacemaker for the others. By 1944 the mile record was driven down to 4 minutes 1.6 seconds by Andersson, and then 4 minutes 1.4 seconds by Hägg. They were declared professionals and their records remained unbroken for nine long years until 1954. The idea that this sub-four-minute mile was impossible was, in my view, a myth. From my knowledge of physiology it seemed preposterous that there was some kind of portcullis that would clang down at 4 minutes 1.4 seconds. If seconds could be clipped off over the past half-century, why would that stop now?

Of course, one difficulty was slow tracks. It is impossible for today’s runners to understand the soggy surface of a wet cinder track in the 1950s when runners can now bounce along on a modern plastic track. Seb Coe, who ran on both surfaces, said, ‘It makes up to four seconds’ difference over a mile.’

I felt that in my running I was now defending a cause. It was a kind of fusion of the Greek Olympic ideal and of the university attitude that Oxford had taught me. I coupled this with my own love of running as one of the most satisfying forms of physical expression. I believed that many other potential athletes could experience this same satisfaction. If my attitude was right then it should be possible to achieve great success and I wanted to see this happen – both for myself and for my friends.

Throughout the winter of 1952–53 I further stepped up the severity of my training programme by intensifying the interval method of running I have already described; Barthel used the same system. I had great admiration for him because he was not a semi-professional maintained by his country’s government. He was a qualified chemist who did his training after his working day was over. He had shown that it was still possible to reach the top and do a normal day’s work in addition – but only just.

In December 1952, John Landy of Australia, who had been knocked out in my heat at the Olympic Games, had startled the world by running a mile in 4 minutes 2.1 seconds. I could hardly believe the improvement from the runner I had known at Helsinki. Landy made no secret of the fact that the four-minute mile was his goal.

If I was going to enter the lists to attack the four-minute mile, the problem was to decide how and where the race should be run. There were four essential requirements: a good track, absence of wind, warm weather and even-paced running. Some have imagined that a four-minute mile might result from normal competition. This could only happen if there was an opponent capable of forcing the pace right up to the last 50 yards: This was what Arne Andersson had tried to do in 1945, to run Gunder Hägg off his feet and to tire his finish. Gunder Hägg held out, overtook Andersson and was able to set up his own world record. Only John Landy could offer me a race of this kind. By the time we ran against each other in the Commonwealth Games in Vancouver in 1954, the four-minute mile might already have been accomplished and it would be too late. It is easier to race an opponent than the clock, but there were no close rivals in Britain so I had little choice but to attempt it before John Landy succeeded.

I had decided some years before that the Oxford track that I had helped to build should be the scene of any attempt at the four-minute mile. The Oxford v. AAA match provided the first opportunity of the 1953 season when I might, at any rate, expect suitable opposition in the early stages of the race. The biggest gamble was the weather and I was taking a great chance in hoping for a suitable day in April or May.

When I ran at Oxford on 2 May 1953, I aimed first to break Sydney Wooderson’s British mile record of 4 minutes 6 seconds, which had stood ever since he set it up in a paced handicap race at Motspur Park on 28 August 1937. R. H. Thomas, a wellknown miler of the time, had ten yards’ start and paced Wooderson for half a mile. There were other runners with up to 250 yards’ start to help him in the later stages. This may seem far removed from the conditions of an ordinary race, but it was the only approach open to him, because there was no runner in Europe at the time who could have extended him.

Chris C was also running for the AAA in the match at Oxford on 2 May 1953 and he agreed to run as hard as he could for the first ¾-mile. It was our first attempt to run four even quarters and our lap times were 61.7, 62.4, 61.1. Then I went into the lead and ran a last lap of 58.4 seconds to give a total time of 4:3.6 minutes, a new British record. This race made me realise that the four-minute mile was not out of reach. It was only a question of time – but would someone else reach the goal before me?

Speculation about the four-minute mile gradually increased through 1953. Details of our lives were splashed across the newspapers here and in Australia. There was even speculation as to whom we might marry. It increased through the summer of 1953. It embarrassed any girlfriends with whom we had dinner or went out dancing, only to find our photos in gossip columns. It was even suggested in one flight of journalistic fancy that I might be suitable for Princess Margaret! Speculation about John Landy was no less. Years later, his wife Lynne said to Moyra, ‘We arranged to meet at a jeweller’s to look at engagement rings and planned to arrive at the jeweller’s shop separately. I stood in the shop for some minutes before I realised that the figure on a sofa hiding behind a newspaper was in fact John trying to disguise the fact that he was about to buy an engagement ring.’

Every time after this when I ran on the track, the public and press expected new records. On 6 May there was a 4 x 1,500m relay attack on the world record, made at Leyton by the Achilles Club, represented by David Law, Chris B, Chris C and myself. We failed to beat the world record, but our combined time of 15 minutes 49.6 seconds bettered by 6 seconds the best time ever made by a British four.

The next race, which I won, was an international mile race at White City on 23 May in 4 minutes 9.4 seconds, with a last lap of 56.6 seconds. This result was greeted with the headline ‘Bannister held back so it looked a race’.

In a match between Oxford and London University on 30 May, the wind was hopelessly strong. I ran a half-mile instead in 1:51.9 minutes, a ground and meeting record.

A week later I was attempting to increase my speed by quarter-miling at the Middlesex Championships at Edmonton. I covered the first bend at a speed which was exceptional for me. Just as I was overtaking a runner in an outside lane I felt a ‘twang’ in my left thigh, like something between a violin string snapping and being kicked by a horse, and limped off the track. I had pulled a muscle for the first time in my running career. Until then I had never been able to understand how athletes pulled muscles. Now it was all too clear – my muscles were unaccustomed to sprinting and I was simply running too fast for them. In the next hour the pain grew worse.

To add insult to the injury, on the same day the American runner Wes Santee threw out a new challenge with a mile in 4 minutes 2.4 seconds in America. There were now three of us in the race, with Landy training in Australia, waiting to make fresh attempts at the record when his own summer season came around in November. How soon could I recover and make another attempt?

The pulled muscle was not as serious as I feared. The muscle fibres were probably not torn, but a small blood vessel supplying them might have burst, which would have made the muscle seize up. M. M. Mays, the AAA masseur, skilfully dispersed any adhesions after I had rested the leg for five days.

In the middle of the following week, after nothing but slow running since the injury, I felt able to run at the speed of a four-minute mile without aggravating the injury. Norris McWhirter persuaded me that I ought to run a paced time trial. To avoid press excitement in case my pulled muscle did not hold out, the event was quietly included as a special invitation race in the Surrey School’s athletic meeting at Motspur Park on the following Saturday, the 27th. I had no idea what would happen, or whether I could last out the distance. I only knew that the same afternoon five hours later, Wes Santee was to run in Dayton, Ohio, and was confidently predicting a four-minute mile.

I was uncertain how I was to be paced, but Don MacMillan, the Australian Olympic runner whom I had first met in New Zealand in 1950, led for two and a half laps. Then Chris B, who had run the first two laps at snail’s pace, loomed on the horizon in front of me, a lap in arrears. He proceeded to encourage me by shouting backwards over his shoulder, just preventing himself from being lapped.

Of course, it could hardly be called a race. It was a mistake. I accept full responsibility for running in it though I did not organise the details. My lap times were 59.6, 60.1, 62.1 and 60.2 seconds, making a total time of 4 minutes 2 seconds. This was the third fastest mile of all time, beaten only by Hägg and Andersson eight years before. My feeling as I look back is one of great relief that I did not run a four-minute mile under such artificial circumstances.

Immediately after the run Chris B and I drove off to north Wales. That night we were sleeping in a hay loft under a skylight, looking at the stars and anticipating a day of climbing, blissfully unaware of the drama which was unfolding in London with the rumpus the secret attempt had caused on Fleet Street.

On 12 July the British Amateur Athletic Board ratified my 4-minute 3.6-second mile run at Oxford on 2 May as a British all-comers and British national record. On my 4-minute 2-second mile run at Motspur Park on 27 June the Board issued a statement to the effect that the time could not be recognised, as they did not see the attempt as a bona fide race.

The news of the rejection of my 4-minute 2-second mile for record purposes brought journalists flocking to the family doorstep. ‘What are your views about it?’ they asked, feeling they were on the brink of a sensation. ‘Surely you must have some views on it? Will you appeal? Only say yes or no!’ ‘No comment,’ I repeated. To say more was dangerous. Anything I said could be twisted. ‘Bannister will not appeal’ is as good a headline as ‘Bannister will appeal’ when a story is hot. If I were once tempted into the slightest utterance, further amplification would be called for and I should find myself in deeper and deeper waters. I stuck to ‘no comment’ instead and evaded all further questions. My own feelings were that I accepted the decision without question. I had doubted that the record would be ratified. As it happened, there was really nothing important at stake. If the time had been under four minutes, the fat would really have been in the fire.

This was my last deliberate attempt of the season. On the same day Santee, under the full glare of publicity, made another attempt to run the four-minute mile and took 4 minutes 7.6 seconds. I could only hope that he would not forestall me before the end of his longer American season.

For the rest of the season I put all ideas of records out of my mind. On 11 July I won the AAA Mile championship in 4 minutes 5.2 seconds, the fastest time for the meeting. After this I was too busy studying to be able to do any serious training, though on 1 August I ran a 4-minute 7.6-second mile in a successful 4 x 1-mile relay attempt on the world record. Chataway, Nankeville, Seaman and I ran a combined time of 16 minutes 4.1 seconds. It was good enough to beat the previous world record of 16 minutes 48.8 seconds, set up by a Swedish team on 5 August 1949. It was also well within the previous British record of 16 minutes 53.2 seconds, made on 4 August 1952 when I was in a British Empire team with Landy, Law and Parnell. Two days later, on August bank holiday in 1952, I ran my fastest half-mile, 1 minute 50.7 seconds, against El Mabrouk of France.

Soon it was the end of our season and of the American season too. But in Australia the summer season was just starting and I waited anxiously for news of John Landy, who was just getting into his stride. This was his second season devoted to record-breaking runs and I felt that it was only a question of time before he ran a four-minute mile.

John Landy’s training programme was more severe than any other middle-distance runner in the world at that time. It involved weightlifting and running every day, up to a total of 200 miles a week. Percy Cerutty, at one time Landy’s coach, has said that Landy has the temperament of a fanatic. He does not consider this a term of disparagement but the highest possible praise accorded to any man. The only other runners he considers to have had this quality are Nurmi and Zátopek. My view is that Cerutty was not entitled to make remarks like this about Landy, even if he was his coach.

In 1953 John Landy had embarked on a course of training that was in the ten-miles-a-session class. He opened the season with a 4.2-minute mile on a grass track in December: a great performance, 0.1 of a second faster than his best of the previous year.

But his harder training and selfless physical ferocity brought precious little improvement. Each week I waited for the news of his times. The tension grew and by April 1954 he had won six races, all in times less than 4.3 minutes, a record achieved by no other athlete in history. Each race, incidentally, was headlined in the British newspapers as ‘Landy fails’. After one race in February he lost heart. ‘It’s a brick wall,’ he said. ‘I shall not attempt it again.’ But he had caught the four-minute fever and was already planning a summer in Scandinavia, where the tracks are perfect and the warm climate such that he could make repeated attempts with all the pace-making he needed.

Landy’s personality intrigued me. I was dependent on the comments of Percy Cerutty, the Australian coach, who said he had seen in Landy

<ext>demonstrations of a character capable of the greatest kindness, gentleness and thoughtfulness, and on the other side – as there is and always must be – a ruthlessness, lack of feeling for others, and a ferocity and antagonism, albeit it is mostly vented on himself, that makes it possible on occasions for John to rise to sublime heights of physical endeavour.</ext>

If all this were true, he would indeed be a formidable opponent, provided all went well and we were both selected for the Empire Games at Vancouver in 1954. A reason for my hesitancy in putting myself in the hands of a coach was that I had no wish for anyone to make any such public statements about me. Franz Stampfl had more discretion and never did this. I could speak for myself.

Over the autumn of 1953 a great change came over my running: I no longer trained alone. Every day between noon and two o’clock I trained on a track in Paddington with a group of recreational runners and had a quick lunch before returning to hospital. In order to do so I was often forced to miss a regular obstetrics lecture at noon. This was the one speciality I was sure I did not want to pursue. At the back of the lecture theatre was a comfortably upholstered leather bench, across which students would habitually recline to escape the lecturer’s line of sight, relaxing sometimes to the extent of sleep. On a wooden panel above it was carved an ironic quotation from Ralph Waldo Emerson: ‘God offers to every mind its choice between truth and repose.’ An unintended irony.

We called ourselves the Paddington Lunchtime Club. We came from all parts of London and our common bond was a love of running. I think my willingness to engage in the social side of running was a sign that I had mellowed. I felt extremely happy in the friendships I made there and these training sessions came to mean almost as much to me as had those at the Oxford track.

In my hardest training Chris B was with me and he made the task very much lighter. On Friday evenings, starting in November 1953, he took me along to Chelsea Barracks where his coach, Franz Stampfl, held a training session. At weekends Chris C would join us and in this friendly atmosphere the very severe training we did became really enjoyable. Franz kept us all amused and usually afterwards the four of us went out to the John Lyons Cornerhouse on Sloane Square to eat baked beans on toast, about the best dish available during food rationing.

I realised that the two Chrises were the only pacemakers who could be relied on to help me attack the four-minute mile early in 1954. Between the four of us, with Franz carefully coordinating our trainings, a strategy emerged as to how this ultimate athletic challenge could be overcome. To use a mountaineering analogy, our plan for the record attempt was for Chris B to take Chris C and me to ‘base camp’ at the half-mile, so that Chris C could then launch me into the attack itself on the last lap. This made both Chris B’s pace judgement and Chris C’s strength and speed over the three-quarter mile equally crucial for success.

In December 1953 we had started a new intensive course of training and ran a series of ten consecutive quarter-miles each week, each in 63 seconds. Through January and February we gradually speeded them up, keeping to an interval of only two minutes between each. By April we could manage them in 61 seconds, but however hard we tried it did not seem possible to reach our target of 60 seconds. We were stuck, or, as Chris B expressed it, ‘bogged down’.

The training had ceased to do us any good and we needed a change. Chris B and I drove up to Scotland overnight for a few days climbing with John Mawe, a doctor friend of Chris’s. Looking back, it seemed bordering on the lunatic to go climbing with a group of friends to make a break from hard training, chancing exposure to cold weather and dodgy food. The ten-hour drive in John’s cramped car, as he himself pointed out, was about as bad an experience as we could put our bodies through so shortly before a big race.

As we turned into the Pass of Glencoe the sun crept above the horizon at dawn. A misty curtain drew back from the mountains and the sun’s sleepless eye cast a fresh cold light on the world. The air was calm and fragrant but it would not stay that way. Rain set in as we set off to climb Clachaig Gully. The gully had turned into a waterfall. Following Chris up the Red Chimney we became utterly drenched, to the extent that Chris worried about my contracting pneumonia from the cold. An athlete in full training is, paradoxically, less resistant to infection than the average person. Chris ordered a fellow climber to lend me dry clothes from his rucksack ‘for the good of British sport’. The climber generously obliged and could later claim a little credit for protecting my health.

We climbed hard for three days, using the wrong muscles in the wrong way! There was an element of danger, too. I remember Chris falling a short way when leading a climb up a rock face depressingly named ‘Jericho Wall’. Luckily, he did not hurt himself. We were both worried, lest a sprained ankle might set our training back by several weeks.

After three days our minds turned to running again. We suddenly became alarmed at the thought of taking any more risks and decided to return. We had slept little and our meals had been irregular. But when we tried to run those quarter-miles again, just three days after our return, the time came down to the magic target of 59 seconds!

It was now less than three weeks to the Oxford University v. AAA race, the first opportunity of the year for us to attack the four-minute mile in a bona fide race. Chris C joined Chris B and me in the AAA team. Chataway doubted his ability to run a ¾-mile in three minutes, but he generously offered to attempt it. I had now abandoned the severe training of the previous months and was concentrating entirely on gaining speed and freshness. I had to learn to release in four short minutes the energy I usually spent in half an hour’s training. Each training session took on a special significance as the day of the Oxford race drew near. It felt a privilege each time I ran a trial on the track.

I never thought of length of stride or style, or even my judgement of pace. All this had become automatically ingrained. There was more enjoyment in my running than ever before: it was as if all my muscles were a part of a perfectly tuned machine. I felt fresh now at the end of each training session.

I had been training almost daily since the previous November and now that the test was approaching I barely knew what to do with myself. For a ¾-mile trial at Paddington there was a high wind blowing. I would have given almost anything to be able to shirk the test that would tell me with ruthless accuracy what my chances were of achieving a four-minute mile at Oxford. I felt that 2 minutes 59.9 seconds for the ¾-mile in a solo training run, without the adrenalin boost, meant 3 minutes 5.99 seconds in a mile race. A time of 3 minutes 1 second would mean 4 minutes 1 second for the mile – just the difference between success and failure. The watch recorded a time of 2.59.9 minutes! I felt a little sick afterwards with the taste of nervousness in my mouth, which I thought of as the release of adrenalin. My speedy recovery within five minutes suggested that I had been holding something back. Two days later I ran a 1.54-minute half-mile quite easily, after a late night, and then took five days’ complete rest before the race.

The chosen day was Thursday 6 May 1954, the day of the AAA race at Oxford. The real problem that faced me was to decide if the weather conditions justified an attempt: the wind was fierce. I went into the hospital as usual and at eleven o’clock I was sharpening my spikes on a grindstone in the laboratory. Someone passing said, ‘You don’t really think that’s going to make any difference, do you?’ Then I rubbed graphite on the spikes so that the wet cinder of the track might be less likely to stick to the spikes.

I decided to travel up to Oxford alone because I wanted time to think. However, when I boarded a carriage at Paddington, there was Franz Stampfl. This was the first of two great moments of chance that day. I could not have wished for a better companion.

Franz is not the kind of coach who, Svengali-like, wishes to turn the athlete into a machine, working to his dictation. We shared a common view of athletics as a means of ‘re-creation’ of each individual, as a result of the liberation of the latent power within him. Franz was like an artist who could see character fulfilment in human struggle and achievement. He was also a coach whom, unlike Cerutty, I could both trust and respect.

We talked, almost impersonally, about the problem I faced. In my mind I had settled this as the day when, with every ounce of strength I possessed, I would attempt to run the four-minute mile. A wind of gale force was blowing which would slow me up by a second a lap, so in order to succeed I must run not merely a four-minute mile but the equivalent of a 3.56-minute mile in calm weather.

I had reached my peak physically and psychologically. There might never be another opportunity like it. I had to drive myself to the limit of my power without the stimulus of competitive opposition. This was my first race for eight months and all this time I had been storing nervous energy. If I tried and failed I should be dejected and my chances would be less on any later attempt. Yet it seemed that the high wind was going to make it impossible.

I had almost decided when I entered the carriage at Paddington that unless the wind dropped soon I would postpone the attempt. Franz understood my dilemma. With his expansive personality and twinkling eye he said, ‘Roger, the weather is terrible, but even if it’s as bad as this, I think you are capable of running a mile in good conditions in 3.56, and that margin is still enough to enable you to succeed today. With the proper motivation, that is a good enough reason for wanting to do it. Remember, if there is only a half-good chance, you may never forgive yourself for missing it. Who knows when or if you may be given another chance, and what about John Landy, soon to race in Europe, and Wes Santee in America? If you pass it up today, you may never forgive yourself for the rest of your life. You will feel pain, but what is it? It’s just pain!’

Franz had almost won his point. Racing has always been more of a mental than a physical problem to me. He went on talking about athletes and performances, but I heard no more. The dilemma was not banished from my mind, but the idea uppermost was that this might be my only chance. He stiffened my resolve. ‘How would I ever forgive myself if I rejected it?’ I thought, as the train arrived in Oxford. I had been wrong to think that the athlete could be self-sufficient.

I arrived at the Iffley Road track and tested two pairs of running shoes. A climbing friend, Eustace Thomas, had had a new set made specifically for me for this occasion, with the weight reduced from six to four ounces per shoe. This small alteration could mean the difference between success and failure. Watching the St George’s flag stand horizontal to the flagpole of a nearby church, however, the chances of success seemed increasingly dismal.

Still undecided as to whether to give it a go, I walked to Charles Wenden’s house in north Oxford for lunch (a ham salad). A lot of my early running at Oxford had been in Charles’s company and I had lived in this house during my later year of research. Now, as then, I appreciated his and Eileen’s calming influence as they went about their business, preparing lunch and looking after their children. The sheer normality of a house with children, who knew nothing of the significance of the event, was soothing.

Later in the afternoon, on my way to the track, I sought out Chris C at Magdalen College. He was two years younger than me and had done his National Service and so was in his last year at Oxford. The sun shone briefly and he was typically upbeat. ‘The day could be a lot worse, couldn’t it? The forecast says the wind may drop towards evening. Let’s not decide until five o’clock.’

We arrived at the track at around 4.30 p.m. At 5.15 p.m. there was a shower of rain. Afterwards, the wind blew equally strongly, but now came in gusts. As Brasher, Chataway and I warmed up, we knew the eyes of the spectators were on us; they were hoping that the wind would drop just a little – if not enough to run a four-minute mile, enough for us to decide to make the attempt.

Failure in sport can be almost as exciting to watch as success, provided the effort is absolutely genuine and complete. But spectators fail to understand – and how can they know? – the intense mental anguish through which an athlete must pass before he can give his maximum effort.

The agony of waiting on the day of the race is almost unbearable. It is so intense that I used to say to myself, ‘Why do I put myself through this? I don’t want ever to do it again.’ Yet in the subsequent exhilaration of winning, the agony of the period of waiting beforehand is forgotten. For some athletes this tension was too great. Lennart Strand, part of the Swedish mile record-breaking team, eventually found the strain of races more than he could bear. After helping Arne Andersson and Gunder Hägg to their records he was forced to retire and became a concert pianist, which he found much less stressful!

The strain of racing is comparable to other situations, like ‘stage fright’ in actors. Speakers at the Royal Institution, where Moyra and I heard many lectures, have by tradition been locked into an ante-room beside the stage before lecturing since an early lecturer became so agitated that he ran away without ever giving his lecture.

At Iffley Road, I could sense that the two Chrises were becoming increasingly irritated with me when, just half an hour before the race, I still had not decided whether to make the world record attempt. They came into the changing room and with one voice pleaded, ‘Come on, Roger, do make up your mind.’ Their impatience was palpable and looking back I understand how difficult it was for them to get in the mood for the race if I went on shilly-shallying, keeping my eye on the flag of the church tower, using it as a wind gauge. I could see I was being unreasonable and so I said, ‘Right, we’ll go for it, we all know what we have to do.’

As we lined up for the start I glanced at the flag again. It fluttered more gently now and the scene from Shaw’s Saint Joan flashed through my mind, how she, at her desperate moment, waited for the wind to change, so that her army could cross the river. This was the second moment of chance, a moment of calm, which I took as a reassuring sign that the wind was indeed dropping.

There was complete silence on the ground … then a false start by Chris B … I felt angry that precious moments during the lull in the wind might be slipping by. The gun fired a second time … Brasher went into the lead and I slipped in effortlessly behind him, feeling tremendously full of running. My legs seemed to meet no resistance at all, as if propelled by some unknown force. We seemed to be going so slowly! Impatiently I shouted, ‘Faster!’ But Brasher kept his head and did not change the pace. I went on worrying until I heard the first lap time, 57.5 seconds. In the excitement my knowledge of pace had temporarily deserted me. After five days’ rest my muscles were full of glycogen, the energy source required by the muscles to contract efficiently. Brasher could have run the first quarter in 55 seconds without my realising it, but for any faster running at such uneven pacing I would have had to pay the price later. Instead, he had made success possible.

At one and a half laps I was still worrying about the pace. A voice shouting ‘relax’ penetrated to me above the noise of the crowd. I learnt afterwards it was Stampfl’s. Unconsciously I obeyed. If the speed was wrong it was too late to do anything about it, so why worry? I was relaxing so much that my mind seemed almost detached from my body. There was no feeling of strain.

I barely noticed the half-mile, passed in 1.58 minutes, nor when, round the next bend, Chataway went into the lead. At three-quarters of a mile my effort was still barely perceptible; the time was 3.07 minutes and by now the crowd was roaring. Somehow I had to run that last lap in 59 seconds. Then I pounced past Chataway at the beginning of the back straight, 300 yards from the finish.

There was a moment of mixed excitement and anguish when my mind took over. It raced well ahead of my body and drew me compellingly forward. There was no pain, only a great unity of movement and aim. Time seemed to stand still, or did not exist. The only reality was the next 200 yards of track under my feet. The tape meant finality, even extinction perhaps.

I felt at that moment that it was my chance to do one thing supremely well. I drove on, impelled by a combination of fear and pride. The air filled me with the spirit of the track where I had run my first race. The noise in my ears was that of the faithful Oxford crowd. Their hope and encouragement gave me greater strength: I had now turned the last bend and there were only 50 yards more.

My body must have exhausted its energy, but it still went on running just the same. The physical overdraft came only from greater willpower. This was the crucial moment when my legs were strong enough to carry me over the last few yards, as they could not have done in previous years. With five yards to go, the finishing line seemed almost to recede. Those last few seconds seemed an eternity. The faint line of the finishing tape stood ahead as a haven of peace after the struggle. The arms of the world were waiting to receive me only if I reached the tape without slackening my speed. If I faltered now, there would be no arms to hold me and the world would seem a cold, forbidding place. I leapt at the tape like a man taking his last desperate spring to save himself from a chasm that threatens to engulf him.

Then my effort was over and I collapsed almost unconscious, with an arm on either side of me. It was only then that real pain overtook me. It was as if all my limbs were caught in an ever-tightening vice. Blood surged from my muscles to my brain and seemed to fell me. I felt like an exploded flashbulb. Vision became black and white. I existed in the most passive physical state without being quite unconscious. I knew that I had done it before I even heard the time. I was surely too close to have failed, unless my legs had played strange tricks at the finish by slowing me down and not telling my tiring brain that they had done so.

The stopwatches held the answer. The announcement came from Norris McWhirter, delivered with a dramatic, slow, clear diction: ‘Result of Event Eight: One mile. First, R. G. Bannister of Exeter and Merton Colleges, in a time which, subject to ratification, is a new Track Record, British Native Record, British All-Comers Record, European Record, Commonwealth Record and World Record… Three minutes…’ The rest was lost in the roar of excitement. I grabbed Brasher and Chataway and together we scampered round the track in a burst of happiness. We had done it, the three of us!

We shared a place where no man had yet ventured, secure for all time, however fast men might run miles in future. We had done it where we wanted, when we wanted, in our first attempt of the year. In the excitement my pain was forgotten and I wanted to prolong those precious moments of happiness.

I felt suddenly and gloriously free from the burden of athletic ambition that I had been carrying for years. No words could be invented for such supreme happiness, eclipsing all other feelings. I thought at that moment I could never again reach such a climax of single-mindedness. I felt bewildered and overpowered.

Looking back at the lap times, it becomes clear we had come dangerously close to missing our goal, despite each of us playing our parts as heroically as we could. The race started according to plan. Brasher rightly ignored my shouted instruction for him to run faster at a time when his pace judgement was in fact excellent. He managed the half-mile in 1 minute 58.3 seconds. Asked afterwards how he judged the pace he replied in his characteristic vernacular: ‘I bloody well couldn’t go any faster!’ He then continued for another half-lap before Chris C took over for one lap between 2½ and 3½ laps.

Only with hindsight is it clear how close to failure we were at that point. The danger is shown by the 220-yard times, which I will list, with the full quarter-mile lap times in parentheses:

Lap 1: 28.7, 29.0 (57.7)

Lap 2: 29.8, 30.8 (60.6)

Lap 3: 31.3, 31.1 (62.4)

Lap 4: 29.7, 29.0 (58.7)

Total 3:59.4.

The fifth 220, when Chris B was tiring, was 31.3 and the sixth 220, after Chris C had taken over, was 31.1. So this pair of 220s took 62.4 seconds, which was 3.7 seconds slower than the last lap. Clearly, if this third lap had been any slower, my sprint over the last 220 yards might well not have been enough to bring us success. There had been a marked but understandable slowing of the pace, making the effort more uneven and less efficient than we had planned.

I had made no promise that I would attempt to break the four-minute mile that day but Norris McWhirter had leaked to the BBC that there could be something afoot on the Oxford track that day which they wouldn’t want to miss. They put two and two together. The reason I didn’t want to make any announcement of my attempt was that if the weather was hopeless, in particular too windy, I would call off any attempt and perhaps just run a 4-minute 5-second mile, which I knew would be a disappointment to the crowd. It meant that I could save myself for the next possible occasion – ten days later at the White City in London. In the event, the BBC only sent a lone cameraman, who stood on the roof of his van parked in the centre of the track and wielded a handheld camera, hence the rather poor quality of the film. Norris had also passed the same message to the dozen or so athletic correspondents whom he knew well, who turned out in force. Enigmatically, Norris just said to them, ‘You might regret it if you were not there.’ We went to Vincent’s Club before I was whisked off by the BBC to the studio in London to appear in a new BBC weekly sports programme with an 8 p.m. deadline. To my surprise the BBC had managed to get the whole of the black-and-white film taken in Oxford only two hours before and it was shown on television that night.

We had an evening of celebration in London, starting with dinner at the Royal Court Club in Chelsea and ending up with our girlfriends in a nightclub until the early morning. At about 2 a.m. we drove off to Fleet Street, where we expected all-night book stands might already have early editions of the papers. Chris B’s driving must have been erratic because a policeman stopped us, and we thought, ‘Oh no! What have we done wrong?’

When Chris wound down his window and stuck his head out, the policeman said, ‘You are driving as though you had lost your way, sir,’ which indeed we had. Then, glancing into the car, he recognised our faces and said, ‘Oh, I recognise you, it’s the three record breakers. Well done! Would you mind giving me your autographs?’ This we happily did and went on our way. When we got the newspapers, we found they had gone to town. There were banner headlines and front- and back-page pieces which the newsrooms had been storing up in advance with long background stories about whether a four-minute mile, like the climbing of Everest was possible. It was rather bad for our egos.

The next morning, my fellow students carried me into the medical school on their shoulders. We learnt later that the news had leaked through to the Oxford Union, where a member interrupted the debate to move for the adjournment of the House for 3.59.4 minutes. The new president of the Union was confused. He refused to accept the motion because ‘notice had not been given’.

The press were on my trail everywhere for the next few days. To avoid their attentions I could only reach and leave my home in Harrow through the back garden, with the help of chairs and ladders over a succession of fences. I escaped to Oxford for a quiet day with my friends the Wendens. When I returned to London, I needed a suitcase to carry off my telegrams and letters. It was the beginning of a series of fan mail and of invitations to open sports centres and running tracks that has continued to this very day.

A week later, the Foreign Office passed on to me an invitation to go to America to appear on various television shows. They hoped I would accept in order to, in that well-worn phrase, strengthen Anglo-American relations. But that was only partly true. The impetus had come from a TV company in New York which had a popular weekly programme called I’ve Got a Secret. Unbeknownst to me and without my consent, I found myself being smuggled out under an assumed name. But the news of my arrival was leaked and, standing on the airport steps in New York, I was surrounded by a ring of reporters. The matter then became vastly more complicated. I was shocked to learn that a cigarette company was sponsoring the TV show. It won’t surprise you to learn that even before Richard Doll’s definitive research incriminating smoking in causing lung cancer, the deadly effects of smoking were well known medically. I had never smoked. The Foreign Office now took over the whole management of my tour and had by then already paid my fare and covered my expenses in New York. I made one interview after another and was presented with a colossal trophy valued at hundreds of pounds for the first person to run a four-minute mile. I suppose, the donors hoped and expected it to be won by an American. I handed it back and got them to prepare a modest replica the size of an egg cup costing $25, the amount to which an amateur athlete was entitled. One day I was taken up in a New York Harbour Authority helicopter and we skirted round sky scrapers like a giant busy mosquito, slipping under bridges and buzzing the Statue of Liberty.

My trip was summed up well by a formal statement by a Foreign Office minister. Less formal was a comment made in the Oxford Union a week later: ‘You can hardly give a girl a bunch of flowers nowadays without endangering her amateur status.’ In 1956, Wes Santee lost his amateur status for receiving expenses above the maximum allowed, as had Gunder Hägg during the war. This shows just how careful I had to be, that it could happen almost inadvertently.

The four-minute mile was a team achievement in which all of the members – me, Chris B, Chris C and Franz Stampfl – played crucial parts, as well as the faithful McWhirters, who kept us apprised of Landy and Santee’s every attempt. Without any one of us, it would not have been run on 6 May 1954, soon enough to forestall foreign rivals and bring the achievement to Britain.

Each of our relationships with Franz as a coach differed. The closest was Chris B, frustrated by his ‘failure’ at Helsinki, putting himself entirely in the hands of Franz Stampfl, who persuaded him that if he followed exactly the training regimes Franz would provide, he would win a gold medal in the steeplechase at Melbourne in 1956.

Chris C knew that the boredom of training alone was too much and so he joined Brasher at the Duke of York’s barracks, where he was introduced to Franz, with whom he planned his training in a much more general way than Chris B. There was no British runner other than Chris Chataway who could have paced the latter part of the race.

Chris B and Chris C were very good friends, coming from the same background of Oxford and Cambridge athletics. Brasher and I had toured America in 1949 when I was captain of the combined Oxford and Cambridge team to Princeton, Harvard, Yale and Cornell. I had also beaten him when he represented Cambridge in the 7½-mile 1949 Oxford v. Cambridge cross-country race, but we were not track rivals because he was clearly better than me over longer distances. By the time Chataway went up to Oxford I had graduated and was doing research. A photograph now in the National Portrait Gallery shows my arms round the two Chrises after the race. My gratitude to them is absolutely evident. It was clear then and has been ever since.

We all had a common aim and shared the success. Chris B, Chris C and Franz Stampfl were all very generous in the support and companionship they offered me during training. The secret, I think, was that we realised it would be a first for Britain, a national achievement, and for British athletics. It was old-fashioned patriotism in the best sense, which is less popular today.

There was another element firing me and perhaps the Chrises too. We were members of the generation that had been at school during the war. I was acutely conscious of the men only two years older than me who had fought and been killed, never having the chance to show what they could achieve both in sport and the rest of their lives. I believe this spurred me to grasp every opportunity I had, and to seek some way of showing that had I been older, I might have perhaps displayed at least some of their spirit. Now in a civilian world the question had become – could I show this by achieving this historic target in athletics?

Chris Brasher was a year older than me and the toughest and most determined runner of the trio; the three musketeers, as some called us. However, in 1954 he was then basically a climber and a cross-country runner, not a miler. He also had the most confidence, sure that his will power and hard work would bring him success. His father had served in the British Empire as an engineer, directing the laying of telephone cables in the Middle East in the 1930s while his children attended boarding schools in England. Chris had run at Rugby School and there, at the age of sixteen, ran in the longest schoolboys’ race in Britain, the Crick Run, over ten miles. He had also taken up mountain climbing while at school. After graduating in Engineering at Cambridge, he had joined an expedition to Greenland and then started work in London for the Mobil Oil Company.

Under Franz’s direction, Brasher went on to win the 1956 Olympics as a steeplechaser. After years of struggling with variable form and frustrating injuries, he finally took the gold that his efforts deserved. The victory only came after an agonising wait while a protest that he had obstructed another runner was dismissed. In a piece for the Sunday Times praising his victory, I wrote, ‘It lifted a huge personal burden from his shoulders and, in his own words, freed him from the imprisonment he had felt in his own body.’ It was also an important symbolic victory. With the Soviet Vladimir Kuts, supported entirely by his country and training up to five hours every day, winning both the 5,000m and the 10,000m, amateur runners looked in danger of extinction. That extinction may now have come about, but at the time Brasher’s gold medal gave hope to a generation of athletes still simultaneously supporting separate full-time careers.

There followed a successful career as a journalist for The Observer and as a BBC producer. However, when the history of the twentieth century is written, it is his creation of the London Marathon for which he will be primarily remembered. Modelling it on the New York Marathon, he and co-creator John Disley, his fellow steeple-chase runner, realised that London had more historic sites than New York. Capitalising on the running revolution which had started in America in the 1960s, a London Marathon would be a winner. But Chris B had to fight fierce opposition from London authorities and the police to get it off the ground. It was only because of his bullet-headed tenacity that he won the day. Within a few years it became the largest marathon in the world, with 40,000 runners and many turned away each year. Sadly Chris B died of pancreatic cancer in 2003, after a brave battle.

Chris Chataway was rightly thought of as the most glamorous of the trio, having an air of nonchalance and sophistication, marked by publicly smoking an occasional cigarette. He always had immense charm. His father had worked as a pilot in the First World War, then a test pilot and finally as an overseas civil servant in the Sudan Political Service. The challenging climate had led him to early retirement. Sadly, he had returned to England with heart disease and was ill at home for several years before he eventually died in 1955. As the oldest of four children, much of the guidance and financial control fell upon Chris’s shoulders, protecting his three younger siblings, who were all educated privately.

Chris had gone to Sherborne School and was more of a boxer than a runner at first until he saw Zátopek winning the 5,000m in the 1948 Olympics. He immediately stopped buying Boxing Weekly to read Athletics Weekly instead. He then completed his National Service with the Royal Green Jackets, before going up to Magdalen College, Oxford, where his uncle had been president, in order to read history. While at Magdalen, he concentrated on sport and, as I had four years before, became president of the Oxford University Athletic Club.

After Finals he joined Guinness as an executive trainee. At first he lived at the company’s headquarters in Hanger Lane, Ealing, where the nearby playing fields were convenient for training. The executive trainees at Guinness were given the name ‘brewers’ and regularly lunched with the chairman, Sir Hugh Beaver. One day, when Sir Hugh had spent the weekend grouse shooting, he asked, ‘Who can tell me how fast those wretched birds can fly?’ Chris said he didn’t know, but he knew someone who did – thinking of Norris McWhirter, whose memory was encyclopaedic. ‘Bring him to lunch,’ Sir Hugh Beaver said. When they met, Sir Hugh was both astonished and fascinated by how much Norris knew, apart from the speed of flight of the grouse. This was the start of the close relationship between Sir Hugh and Norris which led to the Guinness Book of Records, now published in fifty-two languages, which still has the largest annual sales of any book except the Bible.

I once visited Chris C at his home in Woking. He took me running round some of his training circuits, through its neighbouring heath and woodland. I simply could not match him. By 1952 he had become Britain’s most promising three miler and 5,000m runner. But he had missed winning a medal in Helsinki, probably since, like me he was undertrained. He tripped and fell on the last bend through fatigue, but valiantly got up and came fifth in the race which was won by Emil Zátopek. I believe this left him still fiercely ambitious for athletic fame, though he wanted to limit his running career to only a few more years.

Though the 5,000m was his best distance, he had already run a 4.10-minute mile and, perhaps like every middle-distance runner of our generation, hoped that the four-minute mile would sooner or later be within his own compass. He did go on to break the four-minute mile himself a year later in the Emsley Carr mile at the White City, which was won by Derek Ibbotson and Brian Hewson in a dead heat. A sub-four-minute mile was not realistic for Chris B, though he did admit after the four-minute mile was over to having a dream of completing the first half-mile and then somehow carrying on at the same pace and breaking the barrier himself. So the two Chrises, despite having their own ambitions, agreed to be pacemakers, playing the role of supporting cast, helping me to break four minutes.

Chris C defeated Vladimir Kuts and set up a new world record for 5k in a dramatic duel under floodlights, one of the most iconic races of the 1950s, and an event which earned him the BBC Sports Personality of the Year award. He ran in the Olympic 5,000m in Melbourne in 1956 but was not at his best. He got into the final though did not manage to make the top ten and retired soon after.

Chris’s handsome and debonair impression led many to underestimate his abilities on first meeting. He became the first television newscaster for ITV with Robin Day, then launched into politics. Underlying his wish to be an MP was a great idealism and compassion, which found its early fruits in his contribution towards resolving the post-war refugee problem – the distressed people swirling about Europe. For this he was awarded the rare honour of the Nansen Medal. He had two spells as a Conservative MP, first between 1959 and 1966, during which time he held the seat at Lewisham North and was briefly Junior Education Minister. He returned to be elected as MP for Chichester in 1969 and became Ted Heath’s Minister for Posts and Communications in 1970. At one point he incurred the wrath of Opposition leader Harold Wilson for sacking a favoured trade unionist; political colleagues attest to his firm handling of such difficult situations. After a period in opposition he decided to retire from politics and went into banking. His final appointment was as chairman of the Airports Authority, following which he was knighted. He lent his vision and knowledge to many charities. When his son Adam started a water scheme for Ethiopia in 2010, Chris, then nearly eighty, ran in the Great North Run to raise funds for it. He was very much loved by his family – indeed, one son said that above all his father’s achievements he will remember him as a good father. I knew that after a long illness he was gallant to the end.

Franz Stampfl had been the focal point of our team. He was a handsome, debonair Viennese Rex Harrison. He started with Brasher, whom he had coached for several years since Helsinki, and then Chataway for a season, by the time I joined them in October 1953. When Franz first came to Britain at the age of seventeen, he was a promising javelin thrower and skier in his native Austria, but he was interned at the outbreak of the war. In 1940, along with other aliens, he was bound for Australia on what amounted to a prison-ship, the Demera Star. After leaving Liverpool, the ship was torpedoed and Franz survived several hours in the ice-cold water before he was picked up. To us, who had missed the war, the knowledge that he had faced death and survived through courage and endurance gave his words of exhortation a unique force. But more important, he radiated charm, humour and enthusiasm, all vital in coaching where a large part of a coach’s success depends on inculcating self-confidence into his athletes, just as I was learning how important the same qualities were for a doctor. He became a freelance coach, renting the Duke of York’s army barracks in Chelsea in the evenings. I went weekly with the Chrises to the sessions he ran here, usually running 400m fast and slow, totalling twenty laps, or five miles.

The need for coaching varies greatly between different sports and the different disciplines within each. Track athletes generally need less coaching than sportsmen in the more technical hurdling and field events which had been Franz’s real specialty until then. By the time Franz and I had met, I had run for eight years. But I knew to my cost I had made mistakes in planning my training for Helsinki. Franz had the measure of my character; he knew I needed to be handled on a loose rein and also had the insight to know what was needed to increase my strength and confidence for the following May.

Each week through the winter of 1953–54 he watched our interval running, noting the times we had done and judging how hard it had been to achieve them. He approved the climbing break with Chris B when we seemed to be getting ‘stale’. Unlike Landy’s Percy Cerutty (from whom Landy parted company) Franz never commented to the press on my progress or running plans or that a four-minute mile record attempt might soon be made. He was never authoritarian in his advice or directions. Franz was concerned with athletics as a liberating force because it is an individual pursuit: there may on occasion be records to be broken and medals to be won, but mostly there is fun in company, and, in attempting to better one’s own performance, no matter how modest. Franz understood this and instilled this attitude of individualism among his athletes. I shall always regard the crux of his contribution that, on the day of the race, he gave me the self-belief that despite the bad weather I could break the four-minute mile, and I believed him.